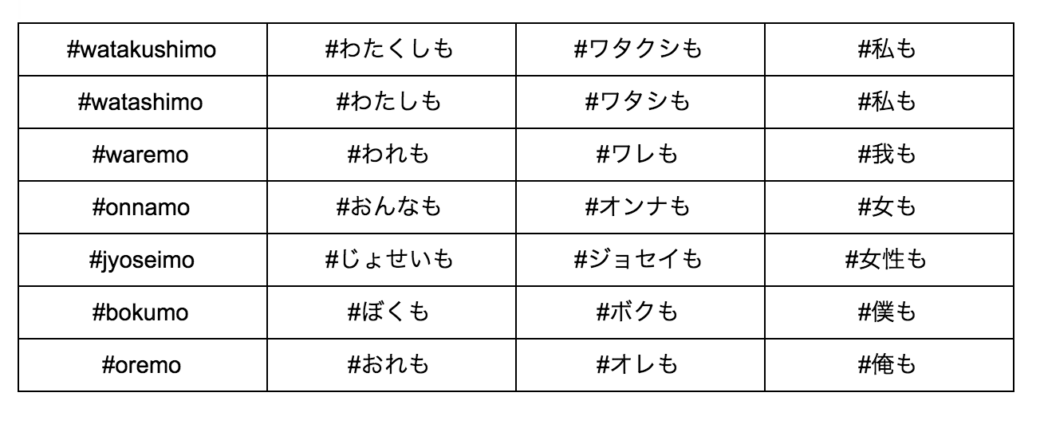

I was thinking about the #metoo movement and how it would translate linguistically in Japan. My initial response was to look it up on instagram in Japanese and then I thought, how is this going to work… The personal pronoun “me” in Japanese could take so many different forms….

- Watakushi

- Watashi

- Ware

These three begin with the more effeminate to least efiminate. Although the second and third option could be used by men as well. Then I thought, perhaps in Japanese it would make sense to use the gender neutral English word “me” and combine it with the Japanese word for “too” mo も. #meも

Or maybe the gendered vocabulary word for women:

- Onna

- Jyosei

Heck, maybe the typical male pronoun (used by some women in subculture):

- Boku

- Ore

Then there’s the use of romaji, katakana, hiragana, or kanji. Does the use of katakana or hiragana, show something different from the use of Kanji?

Since the #metoo movement is already in English, there isn’t a need to reinvent the hashtag, but for the sake of linguistic relativity, maybe there is? What emotion is expressed in these different hashtags, defined in Japanese?

An article in the Japan Times, published on November 25th 2017 talks about the potential “confusion” in media. I believe there are traditional cultural norms and and legal consequences that contribute to any “confusion,” but perhaps a contribution to this is the prominence of the missing gender neutral “me” in the Japanese vocabulary. (ya, kinda stretching it)

Needless to say it seems that any confusion about #metoo will disappear in Japan quickly. And I presume the hashtag #metoo will be favored as it syncs with the other social media messages and statements by sexual victims. An article from December 22nd, 2017 in the Asahi Shinbun, highlights the blogger and writer, Ha-Chu, who shared her experiences of harassment on social media. Further engaging the Japanese public in the movement #metoo.